About 10 minutes into the first class meeting…..”I expect all of you to come to class prepared…”

Yawn. *clicks back to Facebook tab*

Prepared to do what? Listen to a lecture for an hour every day? How do I need to prepare for that beyond making sure my laptop battery is fully charged?

Or perhaps, we should ask (and expect) our students to show up prepared for an active class period full of questions, problems, what-ifs, discussions, and ultimately some answers. So how do we do that? I try my best to follow Robert Talbert’s guide to creating learning objectives. Seriously, that little blog post may be one of the best explications of how to design effective, active classrooms that’s ever been produced

To provide an example, I’ll return to the “difference between HP and LP supercells” outcomes I wrote about last fall. In a course unit on supercell archetypes where we want students to “know the difference between LP and HP supercells,” we might come up with these:

“At the end of this section, students will be able to:

– state the physical differences between LP, classic, and HP supercells;

– recognize the different overall structure between the conceptual models of the three types;

– identify which types are more/less likely to produce tornadoes, strong “straight-line” winds, and large hail;

– describe how environmental wind shear plays a role in modulating supercell type;

– describe how atmospheric water vapor and/or cloud base height play a role in modulating supercell type;

– sketch and label archetypal models of LP, classic, and HP supercells, including cloud and precipitation extent, updraft location relative to precipitation, surface outflows, and the most likely location of a tornado;

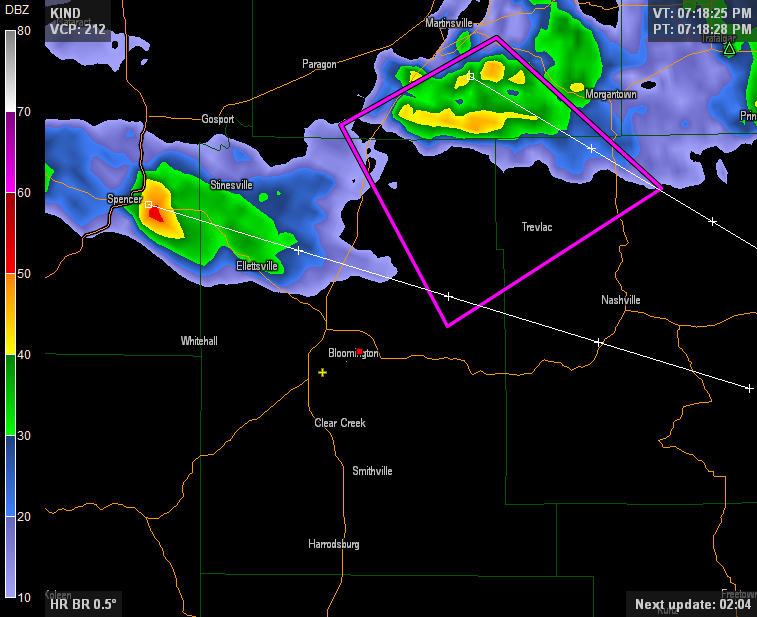

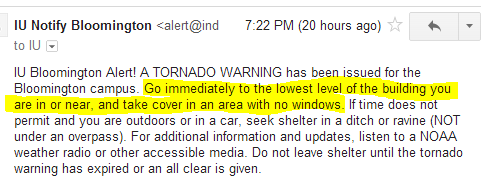

– differentiate between supercell modes using radar data; and

– differentiate between supercell modes in photographs and/or videos.”

Wow. That’s a lot to accomplish…probably multiple classes! I think these are listed roughly in order of increasing difficulty–which is the point–and it would be very easy for me to just sit back and put together 80 or 90 slides that cover everything, and then test students on what I think is important. But I’d rather have them do some Preparation H (homework!) and come to class armed with some basic vocabulary and knowledge. That way, we can get further down the list and spend our class time really diving into and interpreting the radar data, pretty pictures, and complex videos.

So here’s my approach. Before the class period(s) on supercell types, students are expected to be able to perform the first three, maybe four, tasks on that list. Yes, I expect them do be able to do these things before coming to class. The activities for this unit would probably involve reading (Ahrens Extreme Weather and Climate pp. 311-5), looking at additional material (this nice and quick summary by Zach Roberts), and answering short questions online before class (the Just-in-Time method; my example questions for both days of this unit are at the bottom of the post). If students have done the requested assignment, and spent time digesting it and trying to understand it, they should be able to answer these questions easily and will be well prepared for two productive and fun class periods.

Class time would begin with a follow-up on anything that students identify as still unclear, and a review of their answers to the pre-class questions. This typically only requires 10-15 minutes; after that, we move on. For the students who didn’t answer the questions, and didn’t show up prepared, they are going to be seriously lost for the rest of class. It is imperative that students realize their success in class depends on coming to class prepared.

It’s then on me to select the right kind of in-class activities to achieve the last 4-5 objectives in the list. Just a few ideas:

- I might draw three different vertical shear profiles on the board, and ask students to discuss and then draw in what the Cb would look like — barely tilted in weak shear, somewhat tilted in moderate shear, and very tilted in strong shear.

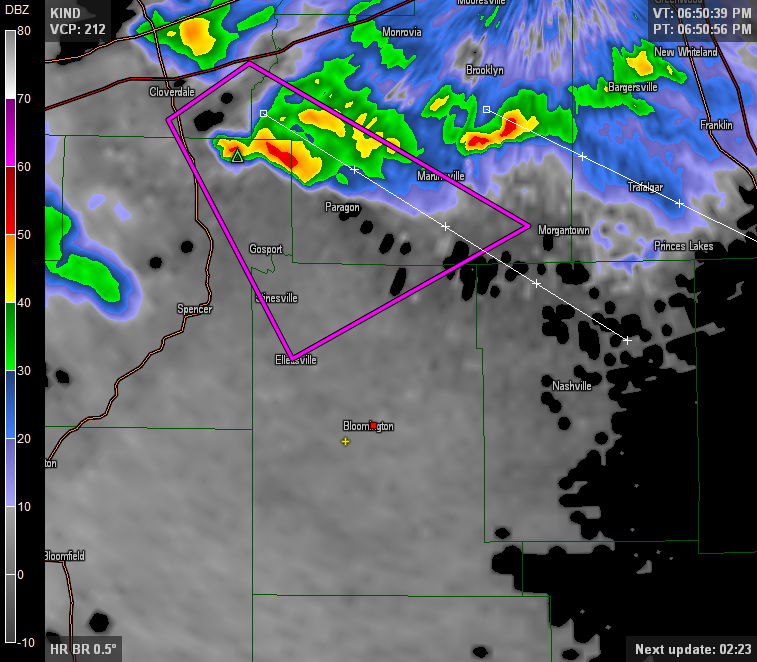

- Provide a printed color copy of reflectivity and velocity data for a classic supercell, to let students draw on and place the mesocyclone relative to the precipitation. (And then identify and label the “hook echo.”)

- Giving the customary supecell schematic with most (or all) of the labels missing, and ask students to label pertinent features.

- Display Figure 7 from Rasmussen and Straka 1998, and ask students to identify which bar graphs correspond to LP, CL, or HP storms.

- Or others, depending on how students respond to the pre-class questions.

This set of learning outcomes, arranged in approximate order of difficulty, is precisely what I would give students as a “study guide” for these class meetings. Exams would include questions that test a range of these outcomes. The ‘A’ students will successfully use photos and videos and radar, the most complex tasks we do; the ‘B’ students will be able to relate supercell types to environment and to label their models; the ‘C’ students may only know the LP/CL/HP differences and the tornado risk from each.

I’ll close with Talbert’s last sentence, which is a superb summary of this process: “This is far from a perfect system, but it’s a reliable way to align learning objectives with the actions you want students to perform and the means you want to use to assess them, and it gives students a key ingredient for self-regulated learning: A clear set of criteria that will tell them what they need to know and how to measure whether or not they know it.”

– – – – –

Students submit answers to these questions online before the first day:

1. The textbook omits large hail from the list of hazards for one of the three supercell types. Which type is less likely to produce large hail?

2. Name two differences you see between the HP and LP photographs in the online reading.

3. Radars can be helpful in determining supercell type (LP/classic/HP). Why do you think that’s the case?

4. Name one thing about either reading that was unclear, confusing, or that you would like clarification on.

Before the second day:

1. The author of this video has declared this storm to be an LP supercell. Do you agree? Why? How would you compare it to the photo and schematic you’ve already seen?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BF8XManeSn0

2. Name one thing that was unclear about yesterday’s discussion that is still unclear, confusing, or that you would like more clarification on.